Introduction

This is the last article about practical routing attacks, after the one against RIPv2 and the one having OSPF as target. Today, we are going to see how an attacker could leverage the BGP protocol on his or her own advantage.

Based on the fact that this topic has been widely covered on great articles online, this one will be nothing more than an introduction; I will let some references in the last section.

Routing theory: precedence

Whenever a router needs to decide where a specific packet has to be forwarded, it has to evaluate its routing table, containing the association between subnets and the gateways that have to be used to reach them.

While in theory subnets never overlap, in practice this is not always the case.

Let’s imagine that we are a router with the following routing table:

- current subnet is 192.168.254.0/24

- subnet A is 192.168.0.0/24, reachable through GW-A 192.168.254.100

- subnet B is 192.168.1.0/24, reachable through GW-B 192.168.254.101

- subnet C is 192.168.2.0/24, reachable through GW-C 192.168.254.102

What happen if a new routing entry is added, defining subnet B1 as 192.168.1.128/25, with GW-B1 192.168.254.200? Basically, the more specific a subnet is, the higher its priority when a packet has to be routed.

Before inserting the entry B1, every host between 192.168.1.1 and 192.168.1.254 is reachable through GW-B; after inserting the more specific route, every host between 192.168.1.1 and 192.168.1.127 is still reachable through GW-B, while every host between 192.168.1.129 and 192.168.1.254 is now assumed to be reachable through GW-B1.

This is not a big deal, unless someone could inject arbitrary, more specific routes inside routers around the world. And yes, this is something that could happen when using BGP.

BGP: the theory

BGP stands for Border Gateway Protocol, that is the gateway protocol that actually runs the whole Internet (it is normally used as exterior gateway protocol, but can be also used as an interior gateway protocol, whenever it is used inside an AS). It is defined, in details, inside different RFCs:

- RFC 4271 defines BGP version 4, that is the one in use today;

- RFC 4760 describes how BGP have been extended in order to be able to deal with protocols different from IPv4, such as IPv6, IPX, etc… (for this reason, the title of the RFC is “Multiprotocol Extensions for BGP-4”).

While the protocol is quite complex, we are more or less only interested in how routers exchange information. Basically, it is only a matter of trust: routers accept new announcements from the peers defined in their configuration, without nearly any check against the content of the announcement.

A weak form of protection for those messages can be applied by using a shared secret between the peers, that is used for cryptographically sign the messages, using an MD5 hash; unluckily, as explained in the previous article, this hashing function is badly broken.

This is only one of the most straightforward BGP vulnerability to understand and exploit, but there are plenty of them. As a proof of this, there is also an RFC (RFC 4272) describing various vulnerabilities and various attack scenarios. Ehm.

BGP: attack analysis

Based on the fact that BGP runs more or less the whole Internet, an attacker could potentially generate huge damages with “little” effort; in the past, various / attacks / proved / that / this / is / absolutely / the / case.

An attacker could in fact diverge the traffic from a specific country, having a specific subnet (or a set of subnets) as destination, gaining the possibility to carry out different attacks, such passive sniffing or Man-In-The-Middle .

There are plenty of different ways to achieve this, but the most straightforward way is to compromise a router, if and only if you are not a malicious actor legally owning the access of one or more routers. Like, you know, a nation.

BGP: exploit lab

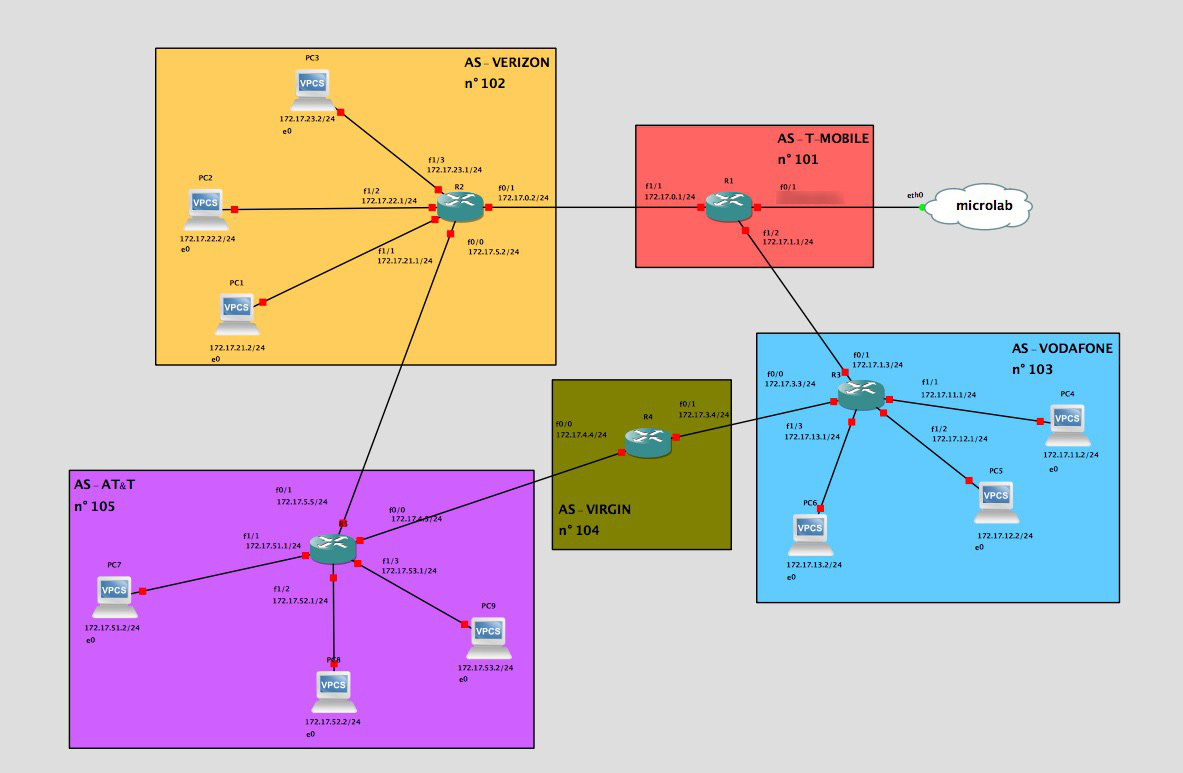

Even in this case, the whole scenario will be simulated using GNS3, with Cisco based firmware emulated inside it. What follows is a screenshot of a possible scenario, using known ISP to identify different AS (the name are randomly selected, as the associated AS number); I just decided to use ISP names because ISPs are an example of entities managing an AS.

BGP: exploit impact

Being able to inject malicious routes is always bad, but it is even worst if this affects the traffic of a whole country or company. Unluckily, while such attacks could lead to huge security problems for the users having their traffic redirected, they are hard to stop, due to weaknesses in the protocol specification.

While there are different companies providing monitor of the BGP routes announced around the world, every user and every company can do their part, by using (or providing), secure protocols, such as the one protected by TLS (e.g.: HTTPS). Unluckily, as you can see in the articles linked below, sometimes this is not enough.

BGP: references

There are plenty of great articles online describing vulnerabilities, attacks and countermeasures online, such as:

- A Survey of BGP Security Issues and Solutions

- Are BGP Routers Open to Attack? An Experiment

- BGP Vulnerability Testing: Separating Fact from FUD v1.1

- Defending Against BGP Man-In-The-Middle Attacks

- Breaking HTTPS with BGP hijacking

- The state of BGP security: Internet plumbing for network security professionals

- BGP Hijinks and Hijacks – Incident Response When Your Backbone Is Your Enemy

UPDATE:

A good friend of mine reminded me also the hijack attributed in 2015 to Hacking Team:

Leave a comment